Game design is the process of designing the content and rules of a game in the pre-production stage and

involves concepts such as gameplay, environment, storyline, and characters. Game design requires artistic

vision, technical knowledge, and an understanding of how players will interact with the game.

A

game designer

creates the core mechanics of a game, including its rules, objectives, challenges, and rewards. They

also

design the user interface and overall user experience to ensure that players can easily navigate and enjoy the

game.

Design is a way to ask questions. Design research, when it occurs through the practice of design itself, is a way to ask larger questions beyond the limited scope of a particular design problem. When design research is integrated into the design process, new and unexpected questions emerge directly from the act of design.

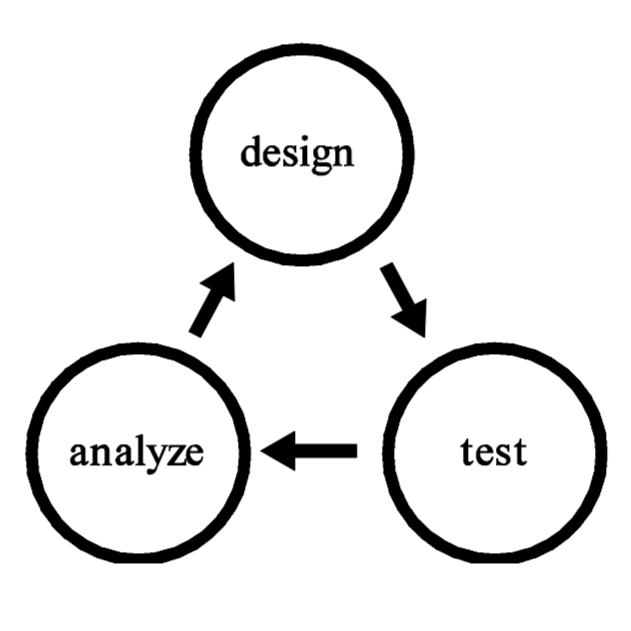

One such research design methodology: the iterative design process, is a design methodology based on a cyclic process of prototyping, testing, analyzing, and refining a work in progress.

In iterative design, interaction with the designed system is used as a form of research for informing and evolving a project, as successive versions, or iterations of a design are implemented.

Because the experience of a viewer/user/player/etc cannot ever be completely predicted, in an iterative process design decisions are based on the experience of the prototype in progress. The prototype is tested, revisions are made, and the project is tested once more. In this way, the project develops through an ongoing dialogue between the designers, the design, and the testing audience.

In the case of games, iterative design means playtesting.

Throughout the entire process of design and development, your game is played. You play it. The rest of the development team plays it. Other people in the office play it. People visiting your office play it. You organize groups of testers that match your target audience. You have as many people as possible play the game. In each case, you observe them, ask them questions, then adjust your design and playtest again.

This iterative process of design is radically different than typical retail game development. More often than not, at the start of the design process for a computer or console title, a game designer will think up a finished concept and then write an exhaustive design document that outlines every possible aspect of the game in minute detail. Invariably, the final game never resembles the carefully conceived original. A more iterative design process, on the other hand, will not only streamline development resources, but will also result in a more robust and successful final product.

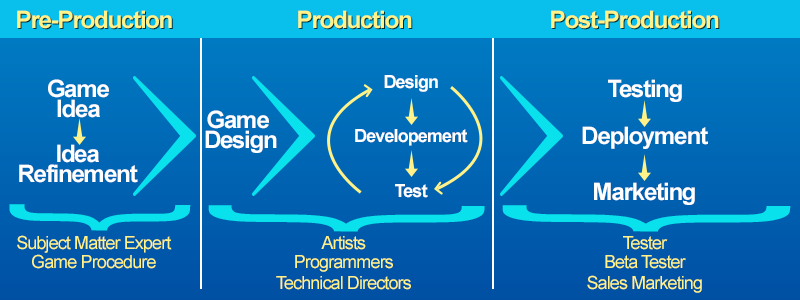

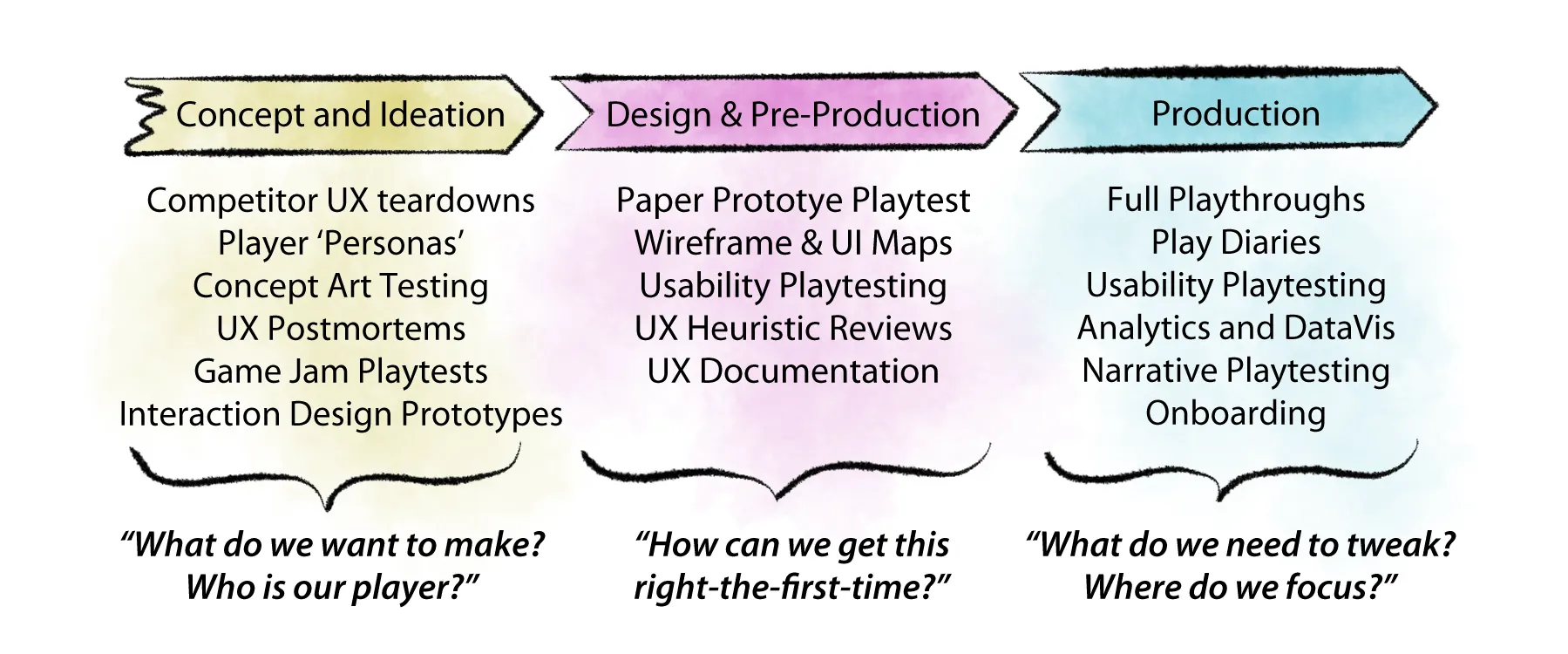

Game development is the process of creating a game from concept to final product. It involves a multidisciplinary approach that includes game design, programming, art and animation, sound design, and testing. Game development typically involves several stages, including pre-production, production, and post-production. During pre-production, the game concept is developed, and the game's mechanics and features are defined. In the production stage, the game is built, and assets such as graphics, sound effects, and music are created. Finally, in post-production, the game is tested for bugs and glitches, and any necessary changes are made before the game is released to the public.

The game development process typically involves several stages, including:

- Concept Development: This stage involves brainstorming and developing the initial concept for the game, including its genre, storyline, and gameplay mechanics.

- Pre-Production: In this stage, the game design document is created, and the game's mechanics, features, and art style are defined. The development team is assembled, and a project plan is created.

- Production: This stage involves building the game, creating assets such as graphics, sound effects, and music, and programming the game's mechanics and features.

- Testing: In this stage, the game is tested for bugs and glitches, and any necessary changes are made to improve gameplay and user experience.

- Post-Production: This stage involves finalizing the game, preparing it for release, and marketing the game to potential players.

In this course, we will be creating both traditional games like board games and card games. For these types of games, we will simply be using pen, paper, and any other physical materials we may need.

However, for video games, we will need to use a game engine. A game engine is a software framework designed for the creation and development of video games. It provides developers with a set of tools and features that simplify the game development process, allowing them to focus on creating the game's content rather than building everything from scratch. Game engines typically include features such as graphics rendering, physics simulation, audio processing, input handling, and scripting capabilities. Some popular game engines include Unity, Unreal Engine, Godot, and CryEngine. These engines are used by both indie developers and large game studios to create games for various platforms, including PC, consoles, and mobile devices.

Unity is a powerful and widely used game engine that provides a comprehensive set of tools and features for game development. It supports 2D and 3D game development, as well as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) experiences. Unity offers a user-friendly interface, a robust asset store, and a large community of developers, making it an excellent choice for both beginners and experienced game developers.

We will be using the free version of Unity, which provides access to most of the engine's features and is suitable for small to medium-sized projects. You can download Unity for free from the official website: https://unity.com/. Make sure to check the system requirements to ensure that your computer meets the necessary specifications to run Unity smoothly.

Game development tools are software applications and frameworks that assist developers in creating, designing, and managing various aspects of game development. These tools can range from game engines to asset creation software, version control systems, and project management tools. Here are some common types of game development tools:

- Game Engines: As mentioned earlier, game engines like Unity, Unreal Engine, and Godot provide a comprehensive set of tools for building and deploying games across multiple platforms.

- Asset Creation Software: Tools like Blender, Maya, and 3ds Max are used for creating 3D models, animations, and textures. For 2D art, software like Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, and GIMP are commonly used.

- Audio Tools: Software like Audacity, FL Studio, and Ableton Live are used for creating and editing sound effects and music for games.

- Version Control Systems: Tools like Git, SVN, and Perforce help developers manage changes to their codebase and collaborate with team members.

- Project Management Tools: Applications like Trello, Jira, and Asana help teams organize tasks, track progress, and manage deadlines.

- Testing and Debugging Tools: Tools like Unity Test Framework, NUnit, and Visual Studio Debugger assist developers in identifying and fixing bugs in their games.

- Collaboration Tools: Platforms like Slack, Discord, and Microsoft Teams facilitate communication and collaboration among team members.

These tools are essential for streamlining the game development process, improving productivity, and ensuring the successful completion of a game project.

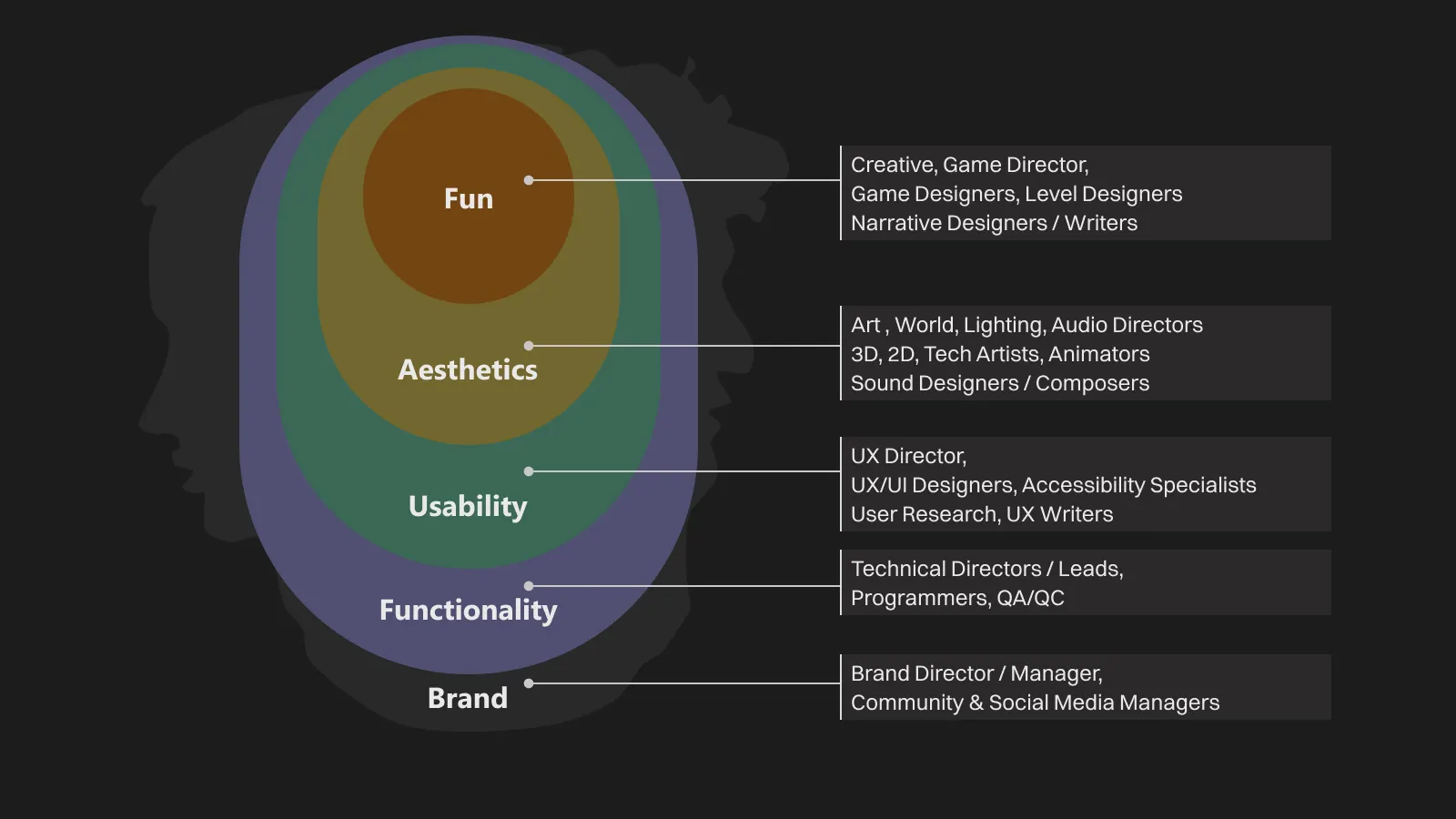

In this class, you will work both individually and in teams to create games. Working in a team allows you to collaborate with others, share ideas, and divide tasks based on individual strengths and skills. Here are some common roles in a game development team:

- Game Designer: Responsible for creating the game's concept, mechanics, and overall design.

- Programmer: Writes the code that brings the game to life, implementing gameplay mechanics, AI, and other features.

- Artist: Creates the visual elements of the game, including characters, environments, and UI design.

- Animator: Brings characters and objects to life through animation.

- Sound Designer: Creates sound effects and music to enhance the game's atmosphere.

- Producer/Project Manager: Oversees the development process, manages timelines, and ensures the project stays on track.

- Tester/QA: Tests the game for bugs and provides feedback on gameplay and user experience.

Effective communication and collaboration are key to a successful game development team. Regular meetings, clear documentation, and a shared vision for the project can help ensure that everyone is on the same page and working towards a common goal.

In this course, you will all learn the basics of game design and development, and you will have the opportunity to take on different roles within your teams. This will give you a well-rounded understanding of the game development process and help you develop skills that are valuable in the industry.

Remember, the most important aspect of game development is to have fun and be creative! Don't be afraid to experiment with new ideas and approaches, and always be open to feedback and collaboration with your teammates.

Over the course of this class, you will learn the basics of game design and development, which can open up various career opportunities in the game industry. Here are some common career paths in game development:

- Game Designer: Responsible for creating the game's concept, mechanics, and overall design.

- Game Programmer: Writes the code that brings the game to life, implementing gameplay mechanics, AI, and other features.

- Game Artist: Creates the visual elements of the game, including characters, environments, and UI design.

- Game Animator: Brings characters and objects to life through animation.

- Sound Designer/Composer: Creates sound effects and music to enhance the game's atmosphere.

- Game Producer/Project Manager: Oversees the development process, manages timelines, and ensures the project stays on track.

- Quality Assurance (QA) Tester: Tests the game for bugs and provides feedback on gameplay and user experience.

- Level Designer: Designs and builds the levels and environments within the game.

- Game Writer/Narrative Designer: Develops the storyline, dialogue, and character development.

- Community Manager: Engages with the game's community, manages social media, and gathers player feedback.

So we know what game design and game development are, but what exactly is a game?

Brainstorm: Try to think of four different games. Write down the names of the games, and a few

words

about what each game is like.

Try to think of games that are very different from each other. For

example,

you might

include chess, tag, poker, and Minecraft. What do these games have in common? How are they different?

So how would you define a game? What makes something a game?

Are there games that do not fit this definition? Are there non-games that do fit this definition?

We can start with the following definition:

A game is something you play.

But this definition is a bit too broad. For example, you can play with a toy, but a toy is not a game. More specifically, a toy is an object that you can play with.

However, this is still quite broad. You might play with a roll of tape, while idly sitting at your desk, but does that make it a toy? Technically, yes, but probably not a very good one. In fact, anything you play with could be classified as a toy. Perhaps it is a good idea for us to start considering what makes for a good toy.

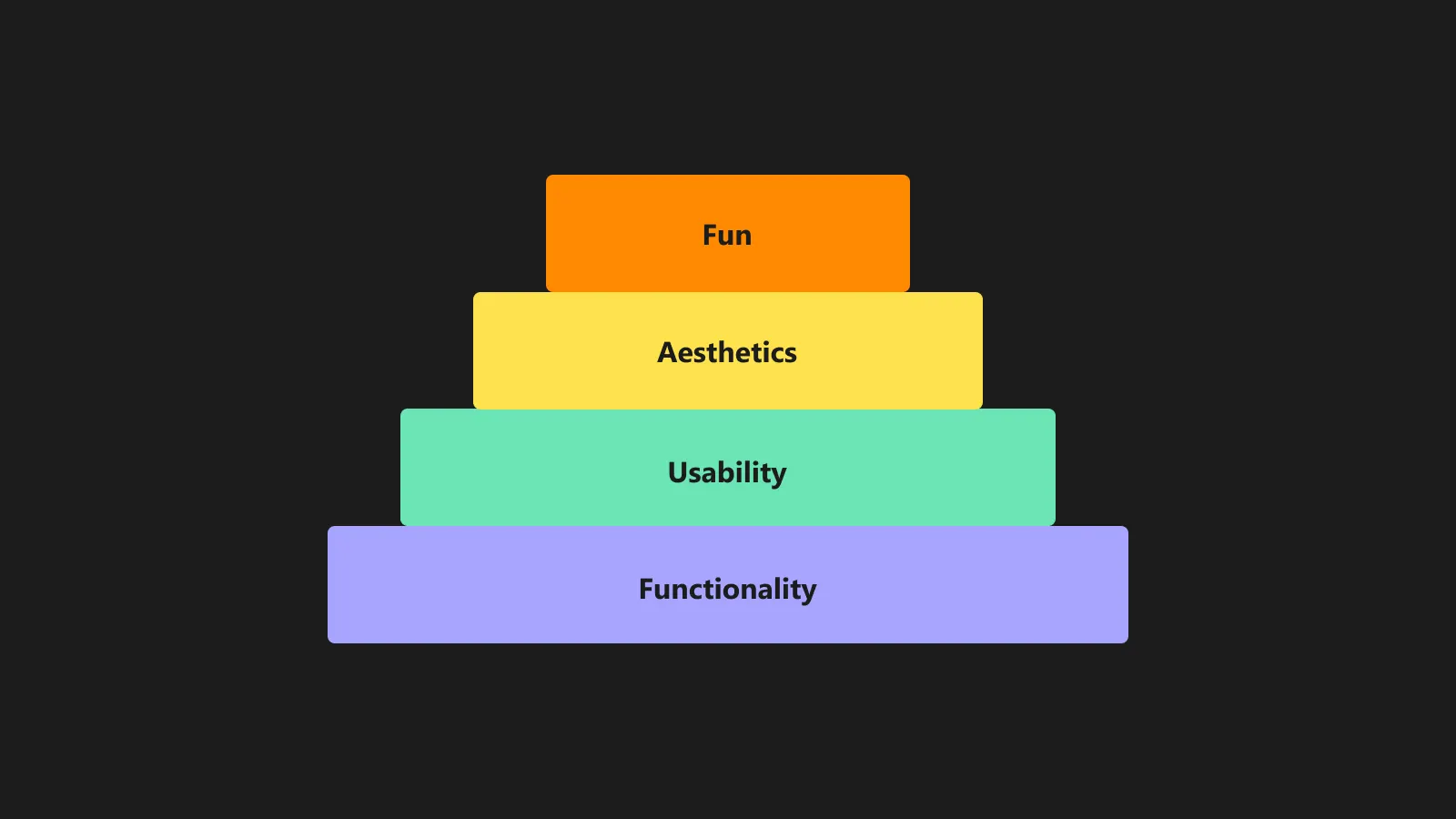

"Fun" is one word that comes to mind in conjunction with good toys. In fact, you might say: A good toy is an object that is fun to play with.

See how we have expanded our definition? Still, what do we mean when we say "fun"? Do we simply mean pleasure, or enjoyment? Pleasure is part of fun, but is fun simply pleasure? There are lots of experiences that are pleasurable, for example, eating a sandwich or lying in the sun, but it would seem strange to call those experiences "fun".

Generally, things that are fun have a special sparkle, a special excitement to them. Generally, fun things involve surprises. So a definition for fun might be: Fun is pleasure with surprises.

Surprise is a crucial part of all entertainment—it is at the root of humor, strategy, and problem solving. Our brains are hardwired to enjoy surprises. In an experiment where participants received sprays of sugar water or plain water into their mouths, the participants who received random sprays considered the experience much more pleasurable than participants who received the sprays according to a fixed pattern, even though the same amount of sugar was delivered. In other experiments, brain scans revealed that even during unpleasant surprises, the pleasure centers of the brain are triggered.

What are some examples of surprises? Here are a few:

- In a card game, you might be dealt a hand of cards that is much better than you expected.

- In a movie, you might be shocked by an unexpected plot twist.

- In a puzzle game, you might figure out a solution that you hadn't considered before.

When designing games, it is important to consider how to create surprises that will delight players. Surprises can come in many forms, such as unexpected challenges, plot twists, or hidden rewards. By incorporating surprises into the game design, developers can create a more engaging and enjoyable experience for players.

Ask yourself the following:

- What will surprise players when they play my game?

- Does the story in my game have surprises? Do the game rules? Does the artwork? The technology?

- Do your rules give players ways to surprise each other?

- Do your rules give players ways to surprise themselves?

Fun is desirable in nearly every game, although sometimes fun defies analysis.

To maximize a game's fun, ask yourself these questions:

- What parts of my game are fun? Why?

- What parts need to be more fun?

So, back to toys. We say that a toy is an object you play with, and a good toy is an object that is fun to play with. But what do we mean by play?

We all know what play is when we see it, but it is hard to express. Many people have tried for a solid definition of what play means, and most of them seem to have failed in one way or another. Let's consider a few:

- "Play is the aimless expenditure of exuberant energy." —Friedrich Schiller

- "Play refers to those activities which are accompanied by a state of comparative pleasure, exhilaration, power, and the feeling of self-initiative." —J. Barnard Gilmore

- "Play is free movement within a more rigid structure." —Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman

- "Play is whatever is done spontaneously and for its own sake." —George Santayana

These definitions are all interesting, but they all seem to fall short in some way. For example, the first definition seems to exclude a lot of play that is not particularly energetic, such as playing chess. The second definition seems to exclude play that is not particularly pleasurable, such as playing a difficult puzzle game. The third definition seems to exclude play that is not particularly structured, such as freeform role-playing. The fourth definition seems to exclude play that is not particularly spontaneous, such as playing a game with rules.

So, what exactly is play?

Play can be summarized in roughly three aspects:

- Perform → players are active participants

- Pretend → Not reality. If games are reality, "they're no longer games -- they're life."

- Not work → Entertainment. "But, in the end, if it isn't fun, it's not a game; it's training or therapy. Or, unfortunately, a waste of time and money."

We've come up with some definitions for toys and fun and even made a good solid run at play. Let's try again to answer our original question: How should we define "game"?

Let's look at four distinct definitions of a game:

According to game designer Kevin Maroney, a game is: A game is a form of play with goals and structure.

We can break this definition down into its parts:

- Play: A game is a form of play. Play is an activity that is performed for its own sake, not for practical purposes. Play is often characterized by imagination, creativity, and spontaneity.

- Goals: A game has goals. Goals give players something to strive for and provide a sense of purpose

and

direction such as score, or winning condition.

A game's goal does not have to produce winners and losers. Cooperative games (such as the games in Sid Sackson's Beyond Competition) allow every player to win if the goals are reached, and in Earthball, a noncompetitive sport invented in the 1970s, play continues indefinitely until the game is won.

Role-playing games (which stretch the definition of games in so many ways) usually have neither winners nor losers. An individual player can achieve his or her own goals without preventing other players from achieving theirs. Players' goals tend to be ad hoc (succeed in a particular mission for the Emperor) or long-term milestones in a career rather than ending points (become a high-ranking noble). A referee's goals are even more nebulous— presenting a credible challenge to the players, advancing a storyline, bringing a particular object into play—and usually revolve around creating an entertaining atmosphere for the players. A referee who views the success of the players as a personal failure and vice versa is not likely to get a lot of repeat play

- Structure: A game has structure. Structure provides the framework within which players can engage in play and pursue their goals. Structure can include rules, mechanics, and systems that govern how the game is played -- e.g. a referee.

Game designer Jane McGonigal, believes that when you strip away the genre differences and the technological complexities, all games share four defining traits:

- A goal: A game is a challenge with a clear outcome. Players must work to achieve a specific objective, whether it's reaching the finish line, solving a puzzle, or defeating an opponent.

- Rules: A game has rules that define how players can interact with the game world and each other. Rules create structure and provide a framework for gameplay.

- Feedback system: A game provides feedback to players based on their actions. This feedback can come in the form of points, rewards, or penalties, and helps players understand how well they are doing in the game.

- Voluntary participation: A game is something that players choose to engage in voluntarily. Players must be willing to participate and follow the rules of the game in order for it to be considered a game.

In the words of the late, great philosopher, Bernard Suits: "Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles"

Game designer Jesse Schell, on the other hand, defines a game as: a problem-solving activity, approached with a playful attitude (what philosopher Bernard Suits calls a "lusory attitude" (from the Latin ludus, play))

We can actually see this theory in the film Mary Poppins (1964), as the titular character is about the sing the song "A Spoonful of Sugar". The children are given the task of cleaning up their room, which is a chore or job, however, Mary Poppins turns it into a game by adding a playful attitude and making it fun.

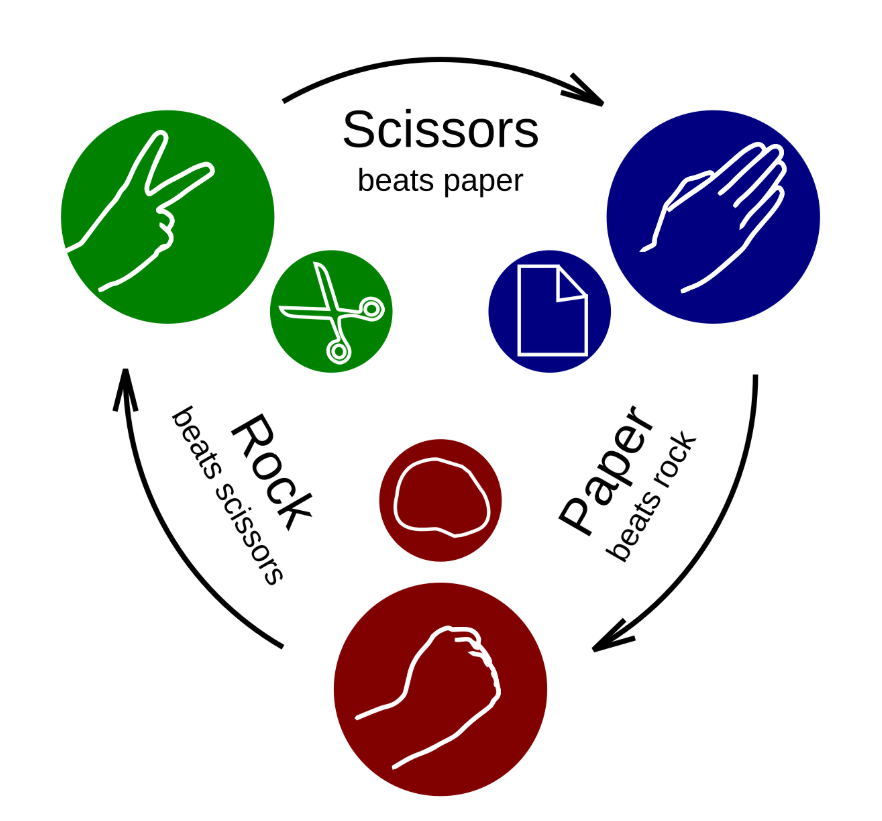

And lastly, according to game designer Chris Crawford, a game is: an interactive, goal-oriented activity, with active agents to play against, in which players (including active agents) can interfere with each other.

Crawford's four main principles are as such:

- A piece of entertainment is a plaything if it is interactive. Movies and books are cited as examples of non-interactive entertainment.

- If no goals are associated with a plaything, it is a toy. (Crawford notes that by his definition, (a) a toy can become a game element if the player makes up rules, and (b) The Sims and SimCity are toys, not games.) If it has goals, a plaything is a challenge.

- If a challenge has no "active agent against whom you compete", it is a puzzle; if there is one, it is a conflict.

- Finally, if the player can only outperform the opponent, but not attack them to interfere with their performance, the conflict is a competition. (Competitions include racing and figure skating.) However, if attacks are allowed, then the conflict qualifies as a game.

In what way do the definitions above inform design?

- Fundamentals - know what to include

- Expanded genres help guide design

- Designing game - purpose - entertainment, competition, etc?

- Constraints limit what the designer can do

Brainstorm: Choose an activity that is not typically considered a game (e.g. waiting for the bus). Now turn it into a game. How will you do that?

What makes a game fun? This is a question that has been debated by game designers and players alike for decades.

Unfortunately, fun is often subjective and hard to describe something that's fun to someone unless they know your tastes and preferences. It's why we use games we enjoy playing to let people know what kind of fun we like to have. We can all agree that fun has an element of pleasure, but what does that really mean?

LeBlanc's 8 Kinds of Fun

Game designer Marc LeBlanc has proposed a list of eight pleasures that he considers the primary "game pleasures".

- Sensation - "To function as an art object, to look, sound or feel beautiful."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as sense-pleasure. This is the most basic kind of fun, and it is often overlooked. Sensation is the pleasure we get from the sensory experience of playing a game. These are games that engage the senses directly. This can include the visual and auditory elements of the game, as well as the tactile experience of using a controller or mouse. RPGs that have minis, terrain, handouts, and things we can touch, pick up, and interact with physically, also exist in this kind of fun.

Seeing something beautiful, hearing music, touching silk, and smelling or tasting delicious food are all pleasures of sensation. It is primarily the aesthetics of your game that will deliver these pleasures.

Sensory pleasure is often the pleasure of the toy. This pleasure cannot make a bad game into a good one, but it can often make a good game into a better one. - Fantasy - "A game to be about something, a vehicle for make-believe."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as make-believe. Fantasy is the pleasure we get from immersing ourselves in a fictional world. This can include the story, characters, and setting of the game. These games don't exist in our world, or if they do the world is changed enough that we can suspend our disbelief and separate from the everyday for a little while. More so, we can take on the personas of people and visit places that only exist in our wildest dreams. D&D is the classic fantasy game. Take up arms and battle mystical and fantastical monsters and foes in a world of swords and sorcery. - Narrative - "The ability for a game to function as a story, to unfold over time... think about a

movie about a sporting event... there's story

content in the sporting event itself. Those things form a narrative."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as drama. Narrative is the pleasure we get from experiencing a story through gameplay. This can include the plot, dialogue, and character development of the game. When it comes to RPGs this element of fun is all encompassing. Every RPG I have ever encountered has narrative as a part of its fun. Often we play RPGs to create or experience stories, from ones that are embedded into the games we're playing where we only have a minimal impact on how they play out, to games that let us build everything about the narrative, and every game that lands somewhere in between. If you enjoy storytelling, then narrative is your kind of fun. - Challenge - "The ability of a game to provide you obstacles to overcome, problems to solve, plans

to form."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as obstacle course. Challenge is the pleasure we get from overcoming obstacles and achieving goals in a game. This can include the difficulty level, puzzles, and combat mechanics of the game. - Fellowship - "All of the social aspects of games; the ability for a game to function as a social

framework. All the ways in which games facilitate

human interaction."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as social framework. Fellowship is the pleasure we get from playing games with others. This can include multiplayer modes, co-op gameplay, and social features of the game. A lot of games are about being social: Apples to Apples, or Cards Against Humanity, are about bringing people together to socialize and the activity is secondary. Yes, there's a win condition in those games, but the experience, humor, and camaraderie that happens during the game is more important than the game itself. If gaming is more about the people and hanging out with your friends, then your fun is found in fellowship. - Discovery - "An opportunity for a game to function as uncharted territory -- you could be a tourist

walking around Disneyland, or you could be

a tourist in the tech tree in Civilization and exploring it. To see a new space and become a master over it

-- that's what I call discovery."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as uncharted territory. Discovery is the pleasure we get from exploring new worlds and uncovering hidden secrets in a game. This can include open-world exploration, hidden items, and Easter eggs in the game. - Expression - "Whether it's how you dress your avatar or it's how you play. Using the game as a

vehicle for expressing yourself."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as self-discovery. Expression is the pleasure we get from expressing ourselves through gameplay. This can include character customization, creative modes, and player choice in the game. - Submission - "The pleasure of a game as a mindless pastime, like the pleasure of knitting or

organizing CDs on a shelf. Some people play

solitaire because it's an interesting problem; some play it for the pleasure of moving the cards around. The

second is submission."

- Marc LeBlanc, MDA Framework

Game as pastime. Submission is the pleasure we get from simply playing a game for the sake of playing. This can include casual games, mobile games, and games that are easy to pick up and play.

These eight types of fun aren't exclusive to each other, more like dials that get turned up and down for

different experiences. Board, Card, Video, and Role Playing Games are all made up of different kinds of fun.

Within those categories of games there are even more variations.

Think of the difference in the

kind of fun

that one has in a game of chess versus a game of Candy Land. Both are board games, but they offer very

different

kinds of fun. Chess is a game of challenge and strategy, while Candy Land is a game of submission and chance.

Different games will emphasize different kinds of fun, and players will have different preferences for which kinds of fun they enjoy the most. As a game designer, it's important to understand these different kinds of fun and to design games that cater to the preferences of your target audience.

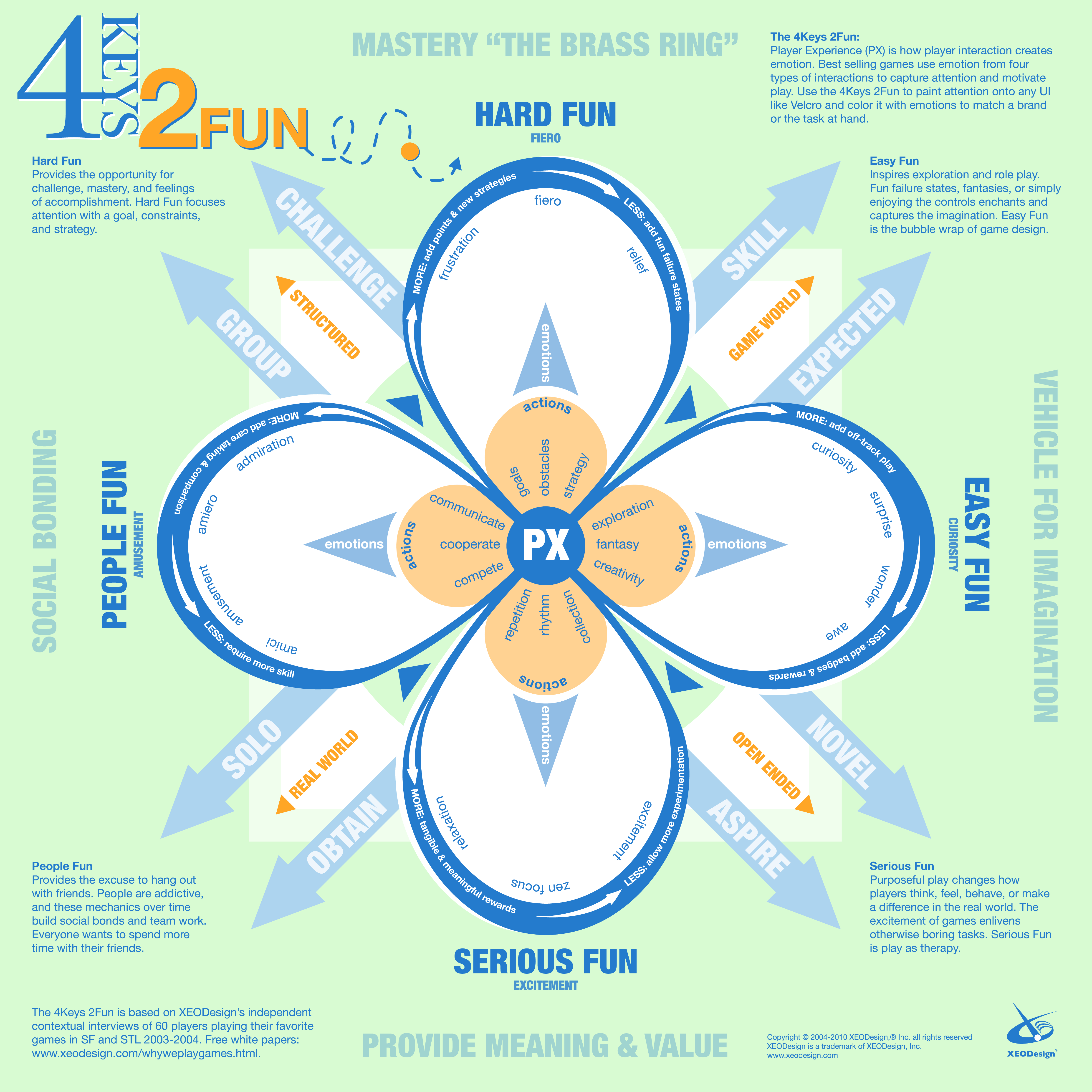

Lazzaro's 4 Keys 2 Fun

Early in 2000 (2003 / 2004), Game designer Nicole Lazzaro and XEODesign (her company), conducted some research into why we play games. They surveyed players and non players, observed them, recorded them and interviewed them to assess the emotions that they felt during play.

They found that there were four main types of fun that players experienced while playing games. These four types of fun are:

- Hard Fun - The pleasure of overcoming challenges and achieving goals. This type of fun is often associated with games that require skill and strategy, such as puzzle games and action games.

- Easy Fun - The pleasure of exploration and discovery. This type of fun is often associated with games that allow players to explore new worlds and uncover hidden secrets, such as open-world games and adventure games.

- Serious Fun - The pleasure of meaningful experiences and emotional engagement. This type of fun is often associated with games that tackle serious themes and issues, such as narrative-driven games and educational games.

- People Fun - The pleasure of social interaction and collaboration. This type of fun is often associated with multiplayer games and games that encourage players to work together, such as cooperative games and party games.

Based on both LeBlanc and Lazzarro, ask yourself the following:

- Which of these pleasures do I most enjoy in games?

- Which of these pleasures do I least enjoy in games?

- Which of these pleasures do I want to include in my game designs?

- Which of these pleasures do I want to avoid in my game designs?

It is useful to examine these 8 different types of fun/pleasures, because different individuals place different values on each one.

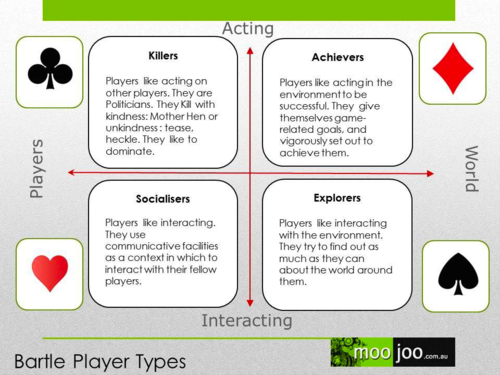

Game designer Richard Bartle, who has spent many years designing MUDs (multi-user dungeons)and other online games, observes that players fall into four main groups in terms of their game pleasure preferences. Bartle's four types are easy to remember, because they have the suits of playing cards as a convenient mnemonic.

- ♦ Achievers want to achieve the goals of the game. Their primary pleasure is challenge. These players are motivated by in-game goals and achievements. They enjoy completing quests, earning points, and collecting items. Achievers are often competitive and strive to be the best in the game.

- ♠ Explorers want to get to know the breadth of the game. Their primary pleasure is discovery. These players are motivated by curiosity and the desire to discover new things. They enjoy exploring the game world, uncovering hidden secrets, and experimenting with game mechanics. Explorers are often more interested in the journey than the destination.

- ♥ Socializers are interested in relationships with other people. They primarily seek the pleasures of fellowship. These players are motivated by social interaction and building relationships with other players. They enjoy chatting, forming alliances, and participating in group activities. Socializers are often more interested in the community than the game itself.

- ♣ Killers are interested in competing with and defeating others. These players are motivated by competition and the desire to dominate other players. They enjoy PvP (player versus player) combat, causing chaos, and asserting their dominance in the game world. Killers are often more interested in winning than in the game itself.

Bartle's taxonomy has been widely adopted in the game industry and has influenced the design of many games, particularly online multiplayer games. By understanding the different player types, game designers can create games that cater to the preferences and motivations of their target audience.

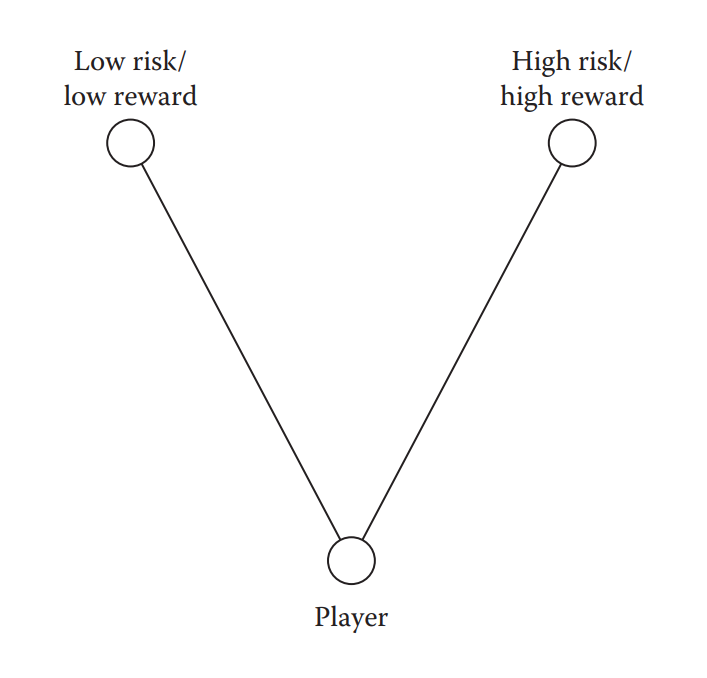

Bartle also proposes a fascinating graph (below) that shows how the four types neatly cover a sort of space:

That is:

- Achievers are interested in acting on the world,

- Explorers are interested in interacting with the world,

- Socializers are interested in interacting with players,

- Killers are interested in acting on players

Here's a video explaining Bartle's taxonomy: Bartle's Taxonomy of Player Types

Ask yourself the following:

- Which of these player types do I most identify with?

- Which of these player types do I least identify with?

- Which of these player types do I want to include in my game designs?

- Which of these player types do I want to avoid in my game designs?

An example of player types:

Player Type Case Studies

Here are some examples of case studies describing a player, based on Bartle's taxonomy, how might they approach a game?

Case Study 1: Chris

Chris spends much of his time in Minecraft (creative mode), building strange contraptions and pushing the game's physics. He also enjoys puzzle games like Portal 2. While he usually plays solo, he sometimes uploads videos to YouTube—not for fame, but because he enjoys it when someone notices the cleverness of his designs.

- What seems most important to Chris when he plays?

- Do you think Chris would enjoy a game with no building or experimentation? Why or why not?

- How does sharing his work with others shape your interpretation of his motivations?

- Explorer: Strong — likes experimenting, discovering "how the game works."

- Achiever: Moderate — enjoys recognition and “accomplishing” quirky projects.

- Socializer: Minor — not very interactive, but he does seek acknowledgment.

- Killer: Minor — not focused on competition or dominance.

Case Study 2: Maria

Maria plays Breath of the Wild, Elden Ring, and Skyrim. She often wanders away from the main quest to explore hidden corners of the world. She enjoys sharing discoveries with friends afterward and appreciates the small achievements the game offers.

- What seems most important to Maria when she plays?

- Do you think Maria would enjoy a game with a strict linear storyline? Why or why not?

- How does her enjoyment of sharing discoveries with friends influence your understanding of her motivations?

- Explorer: Strong — loves exploring and uncovering secrets.

- Socializer: Moderate — enjoys sharing experiences with friends.

- Achiever: Minor — values small accomplishments but not the main focus.

- Killer: Minor — not focused on competition or dominance.

Case Study 3: Jake

Jake plays Valorant, Call of Duty: Warzone, and League of Legends. He loves intense matches and tracking his progress but also enjoys teaming with friends and interacting with viewers when streaming.

- What seems most important to Jake when he plays?

- Do you think Jake would enjoy a game without competitive elements? Why or why not?

- How does his streaming activity shape your interpretation of his motivations?

- Achiever: Strong — driven by competition and personal progress.

- Socializer: Moderate — values teamwork and community interaction.

- Killer: Minor — enjoys competition but not at the expense of others.

- Explorer: Minor — not focused on discovery or experimentation.

Case Study 4: Sophia

Sophia plays Among Us, Animal Crossing, World of Warcraft, and Jackbox Party Pack. She enjoys hosting game nights, coordinating events, and connecting with people. She also values when her group works together to accomplish something meaningful.

- What seems most important to Sophia when she plays?

- Do you think Sophia would enjoy a game focused solely on individual achievement? Why or why not?

- How does her enjoyment of hosting and coordinating events influence your understanding of her motivations ?

- Socializer: Strong — thrives on social interaction and community building.

- Achiever: Moderate — enjoys group accomplishments and meaningful goals.

- Explorer: Minor — appreciates new experiences but not the main focus.

- Killer: Minor — not focused on competition or dominance.

The Bartle Test is a simple quiz that can help you determine your player type. You can take the test here.

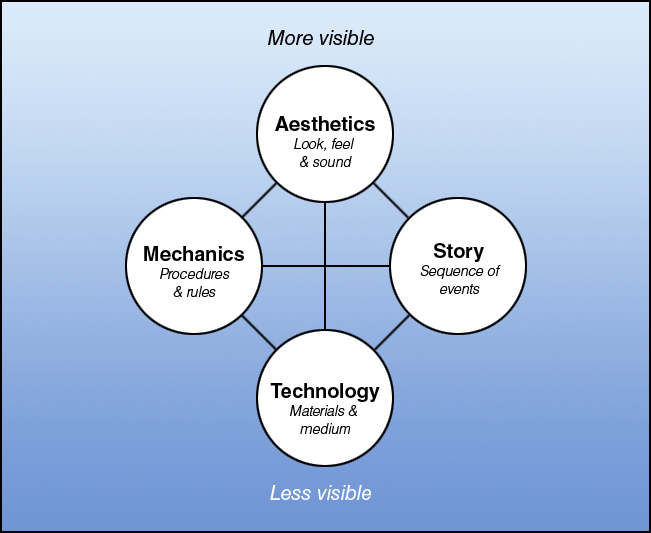

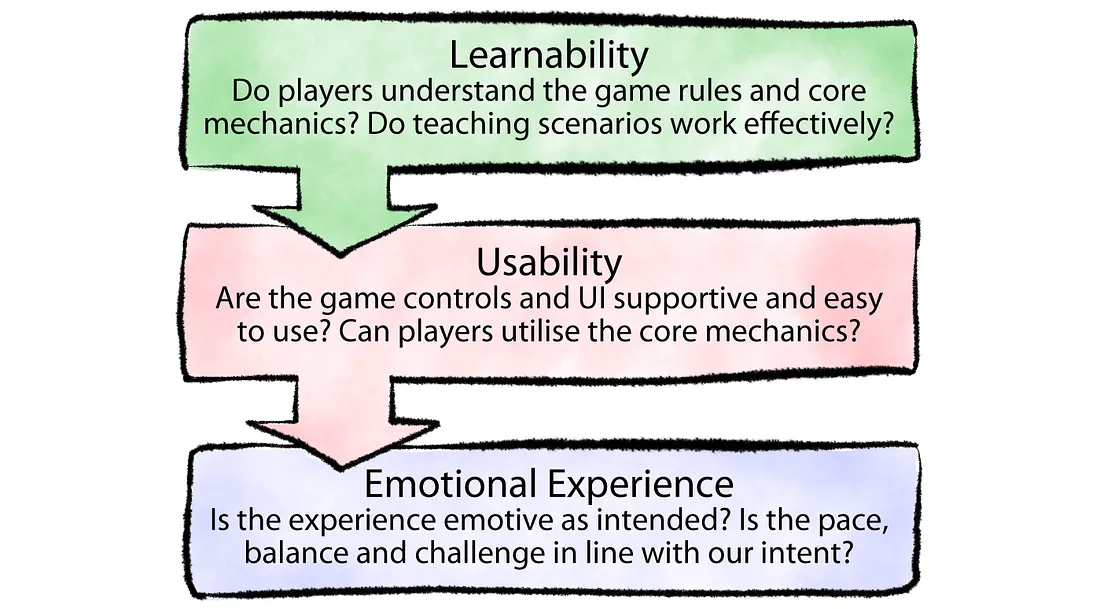

There are many ways to break down and classify the many elements that form a game. One way is to look at the four main elements that make up a game:

- Mechanics - These are the procedures and rules of your game.

Mechanics describe the goal of your game, how players can and cannot try to achieve it, and what happens when they try.

If you compare games to more linear entertainment experiences (books, movies, etc.), you will note that while linear experiences involve technology, story, and aesthetics, they do not involve mechanics, for it is mechanics that make a game a game.

When you choose a set of mechanics as crucial to your gameplay, you will need to choose technology that can support them, aesthetics that emphasize them clearly to players, and a story that allows your (sometimes strange) game mechanics to make sense to the players - Story - This is the sequence of events that unfolds in your game. It may be linear

and pre-scripted, or it may be branching and emergent.

When you have a story you want to tell through your game, you have to choose the mechanics that will both strengthen that story and let that story emerge.

Like any storyteller, you will want to choose the aesthetics that help reinforce the ideas of your story and the technology that is best suited to the particular story that will come out of your game. - Aesthetics - This is how your game looks, sounds, smells, tastes, and feels.

Aesthetics are an incredibly important aspect of game design since they have the most direct relationship to a player's experience.

When you have a certain look, or tone, that you want players to experience and become immersed in, you will need to choose a technology that will not only allow the aesthetics to come through but amplify and reinforce them. You will want to choose the mechanics that make players feel like they are in the world that the aesthetics have defined, and you will want a story with a set of events that let your aesthetics emerge at the right pace and have the most impact. - Technology - We are not exclusively referring to "high technology" here, but to

any materials and interactions that make your game possible such as paper and

pencil, plastic chits, or high-powered lasers.

The technology you choose for your game enables it to do certain things and prohibits it from doing other things. The technology is essentially the medium in which the aesthetics take place, in which the mechanics will occur, and through which the story will be told.

It is important to understand that none of the elements are more important than the others.

The tetrad is arranged here in a diamond shape not to show any relative importance but only to help illustrate the "visibility gradient", that is, the fact that technological elements tend to be the least visible to the players, aesthetics are the most visible, and mechanics and story are somewhere in the middle.

The important thing to understand about the four elements is that they are all essential. No matter what game you design, you will make important decisions about all four elements. None is more important than the others, and each one powerfully influences each of the others.

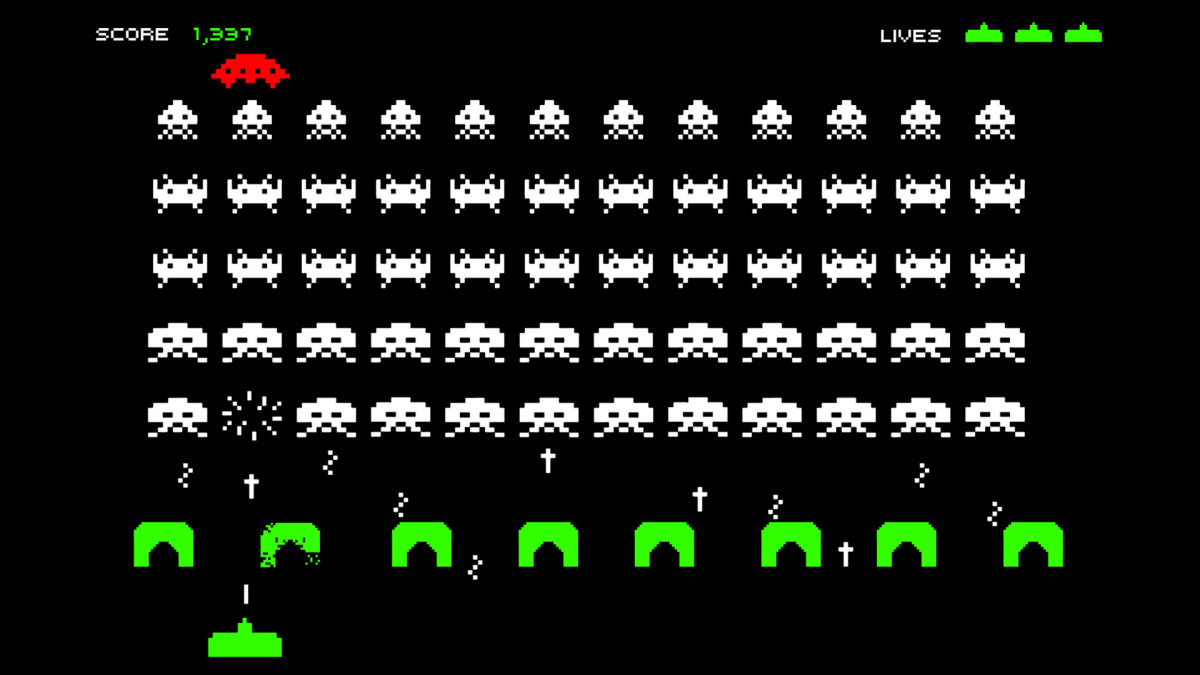

Example: Space Invaders

Consider the design of the game Space Invaders (Taito 1978) by Toshihiro Nishikado. If (somehow) you aren't familiar with the game, do a quick web search so that you understand the basics. We will consider the design from the points of view of the four basic elements:

- Technology - All new games need to be innovative in some way. The technology behind Space Invaders was custom designed for the game. It was the first video game that allowed a player to fight an advancing army, and this was only possible due to the custom motherboard that was created for it. An entirely new set of gameplay mechanics was made possible with this technology. It was created solely for that purpose.

- Mechanics - The gameplay mechanic of Space Invaders was new, which is

always exciting. But more than that, it was interesting and well balanced. Not

only does a player shoot at advancing aliens that shoot back at him, the player

can hide behind shields that the aliens can destroy (or that the player can choose

to destroy themself).

Further, there is the possibility to earn bonus points by shooting a mysterious flying saucer. There is no need for a time limit, because the game can end two ways: the player's ships can be destroyed by alien bombs and the advancing aliens will eventually reach the player's home planet. Aliens closest to the player are easier to shoot and worth fewer points. Aliens farther away are worth more points.

One more interesting game mechanic is that the more of the 48 aliens you destroy, the faster the invading army gets. This builds excitement and makes for the emergence of some interesting stories.

Basically, the game mechanics behind Space Invaders are very solid and well balanced and were very innovative at the time. - Story - This game didn't need to have a story. It could have been an abstract game where a triangle shoots at blocks. But having a story makes it far more exciting and easier to understand.

- Aesthetics - Some may sneer at the visuals, which now seem so primitive, but the

designer did a lot with a little. The aliens are not all identical. There are three different designs, each

worth a different amount of points. They each perform a

simple two-frame "marching" animation that is very effective. The display was not

capable of color—but a simple technology change took care of that!

Since the player was confined to the bottom of the screen, the aliens to the middle, and the saucer to the top, colored strips of translucent plastic were glued to the screen so that your ship and shields were green, the aliens were white, and the saucer was red. This simple change in the technology of the game worked only because of the nature of the game mechanics and greatly improved the aesthetics of the game.

Audio is another important component of aesthetics. The marching invaders made a sort of heartbeat noise, and as they sped up, the heartbeat sped up, which had a very visceral effect on the player. There were other sound effects that helped tell the story too. The most memorable was a punishing, buzzing crunch noise when your ship was hit with an alien missile.

But not all aesthetics are in the game! The cabinet for Space Invaders also had a design that was attractive and eye-catching that helped tell the story of the evil alien invaders.

Part of the key to the success of Space Invaders was that the four basic elements were all working hard toward the same goal — to let the player experience the fantasy of battling an alien army. Each of the elements made compromises for the other, and clearly deficits in one element often inspired the designer to make changes in another. These are the sort of clever insights you are likely to have when you view your design through the Lens of the Elemental Tetrad.

Game Mechanics

Game mechanics are the core of what a game truly is. They are the interactions and relationships that remain when all of the aesthetics, technology, and story are stripped away.

As with many things in game design, we do not have a universally agreed-upon taxonomy of game mechanics. One reason for this is that the mechanics of gameplay, even for simple games, tend to be quite complex and very difficult to disentangle. Attempts at simplifying these complex mechanics to the point of perfect mathematical understanding result in systems of description that are obviously incomplete.

But there is another reason that taxonomies of game mechanics are incomplete. On one level, game mechanics are very objective, clearly stated sets of rules. On another level, though, they involve something more mysterious.

Schell presents a taxonomy to classify game mechanics. These mechanics fall largely into seven main categories, and each one can provide useful insights on your game design.

- Space - Every game takes place in some kind of space. This space is the "magic circle"

of gameplay. It defines the various places that can exist in a game and how those

places are related to one another.

As a game mechanic, space is a mathematical construct. We need to strip away all visuals, all aesthetics, and simply look at the abstract construction of a game's space.

There are no hard and fast rules for describing these abstract, stripped-down game spaces. Generally, though, game spaces:- Are either discrete or continuous

- Have some number of dimensions

- Have bounded areas that may or may not be connected

For example, the game of chess takes place in a discrete space (the 64 squares on the chessboard), which has two dimensions (the X and Y coordinates of the board), and is bounded (the pieces cannot leave the board).

In contrast, the game of billiards takes place in a continuous space (the surface of the table), which also has two dimensions (the X and Y coordinates of the table), and is bounded (the balls cannot leave the table).

A game like the original Super Mario Bros. takes place in a discrete space (the individual screens that make up the levels), which has two dimensions (the X and Y coordinates of the screen), and is bounded (the player cannot leave the screen).

A game like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild takes place in a continuous space (the open world), which has three dimensions (the X, Y, and Z coordinates of the world), and is bounded (the player cannot leave the world).Nested Spaces

Many game spaces feature "spaces within spaces".

Computer-based fantasy role-playing games are a good example of this. Most of them feature an "outdoor space" that is continuous and 2D. A player traveling this space sometimes encounters little icons representing towns, or caves, or castles. Players can enter these as completely separate spaces, not really connected in any way to the "outdoor space" but through the gateway icon.

This is not geographically realistic, of course—but it matches our mental models of how we think about spaces — when we are indoors we think about the space inside the building we are in, with little thought to how it exactly relates to the space outside. For this reason, these "spaces within spaces" are often a great way to create a simple representation of a complex world.

Zero Dimensions

Does every game take place in a space? Consider a game like "Twenty Questions", where one player thinks of an object, and the other player asks "yes or no" questions trying to guess what it is.

There is no game board and nothing moves — the game is just two people talking. You might argue that this game has no space.

But you would be wrong. The mind of the answerer contains the secret object. The mind of the questioner is where all the weighing of the previous answers is going on, and the conversation space between them is how they exchange information.

Every game has some kind of information or "state", and this has to exist somewhere. So, even if a game takes place in a single point of zero dimensions, it can be useful to think of it as a space. You may find that figuring out an abstract model for a game whose space seems to be trivial may lead you to insights about it that surprise you.

When thinking about game spaces, it is easy to be swayed by aesthetics. There are many ways to represent your game space, and they are all good, as long as they work for you. When you can think of your space in these pure abstract terms, it helps you let go of assumptions about the real world, and it lets you focus on the kinds of gameplay interactions you would like to see. Of course, once you have manipulated the abstract space so that you are happy with its layout, you will want to apply aesthetics to it.

If you can simultaneously see your abstract functional space and the aesthetic space the player will experience, as well as how they interrelate, you can make confident decisions about the shape of your game's world.

- Time - In the real world, time is the most mysterious of dimensions. Against our will, we

travel through it, ever forward, with no way to stop, turn around, slow down, or

speed up.

In games, however, time is a mechanic that can be manipulated in various ways.Discrete and Continuous Time

Just as space in games can be discrete or continuous, so can time.

We have a word for the unit of discrete time in a game: the "turn". Generally, in turn-based games, time matters little. Each turn counts as a discrete unit of time, and the time between turns, as far as the game is concerned, doesn't exist. Scrabble games, for example, are generally recorded as a series of moves, with no record of the amount of time that each move took, because real clock time is irrelevant to the game mechanics.

Of course, there are many games that are not turn based, but instead operate in continuous time. Most action video games are this way, as are most sports. And some games use a mix of time systems. Tournament chess is turn-based but has a continuous clock to place time limits on each player.

Clocks and Races

Clocks of varying types are used in many games, to set absolute time limits for all kinds of things.

The "sand timer" used in Boggle, the game clock in American football, and even the duration of Mario's jump in Donkey Kong are different kinds of "clock" mechanisms, designed to limit gameplay through absolute measure of time.

Just as there can be nested spaces, sometimes time is nested, as well. Basketball, for instance, is often played with a game clock to limit the length of total play but also with a much shorter "shot clock" to help ensure players take more risks, keeping the gameplay interesting.

Other measures of time are more relative—we usually refer to these as "races". In the case of a race, there is not a fixed time limit, but rather pressure to be faster than another player. Sometimes this is very obvious, like in an auto race, but other races are more subtle, such as my race in Space Invaders to destroy all the invading aliens before they manage to touch the ground.

There are many games, of course, where time is not a limiting factor, but it is still a meaningful factor. In baseball, for example, innings are not timed, but if the game goes on too long, it can exhaust the pitcher, making time an important part of the game.

Controlling Time

Games give us the chance to do something we can never do in the real world: control time. This happens in a number of fascinating ways. Sometimes we stop time completely, as when a "time-out" is called in sporting match or when the "pause" button is pushed on a video game.

Occasionally, we speed up time, as happens in games like Civilization, so that we can see years pass in just seconds. But most often, we rewind time, which is what happens every time you die in a video game and return to a previous checkpoint. Some games, such as Braid, go so far as to make manipulation of game time a central mechanic.

- Objects/Attributes/States - A space without anything in it is, well, just a space.

Your game space will surely have objects in it. Characters, props, tokens, scoreboards, or anything that can be seen or manipulated in your game falls into this category. Objects are the “nouns” of game mechanics. Technically, there are times you might consider the space itself an object, but usually the space of your game is different enough from other objects that it stands apart.

Objects generally have one or more attributes, one of which is often the current position in the game space.

Attributes are categories of information about an object. For example, in a racing game, a car might have maximum speed and current speed as attributes. Each attribute has a current state.

The state of the "maximum speed" attribute might be 150 mph, while the state of the "current speed" attribute might be 75 mph if that is how fast the car is going. Maximum speed is not a state that will change much, unless perhaps you upgrade the engine in your car. Current speed, on the other hand, changes constantly as you play. - Actions - The next important game mechanic is the action. Actions are the "verbs" of game

mechanics. There are two perspectives on actions or, put another way, two ways to

answer the question "What can the players do?"

The first kind of action is the basic action. These are simply the base actions a player can take.

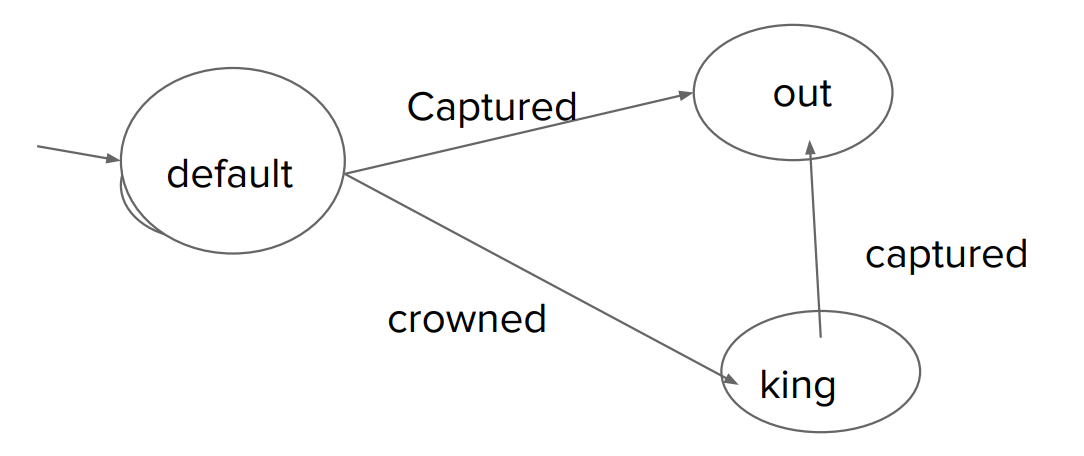

For example, in checkers, a player can perform only three basic operations:- Move a checker forward

- Jump an opponent's checker

- Move a checker backwards (kings only)

The second kind of action is strategic action. These are actions that are only meaningful in the larger picture of the game—they have to do with how the player is using basic actions to achieve a goal. The list of strategic actions is generally longer than the list of basic actions.

Consider some possible strategic actions in checkers:- Protect a checker from being captured by moving another checker behind it

- Force an opponent into making an unwanted jump

- Sacrifice a checker to trick your opponent

- Build a "bridge" to protect your back row

- Move a checker into the "king row" to make it a king.

As you can see, strategic actions are more complex and involve a deeper understanding of the game mechanics. They often require planning and foresight, as well as an understanding of the opponent's potential responses.

- Rules - The rules are really the most fundamental mechanic. They define the space, the

timing, the objects, the actions, the consequences of the actions, the constraints on

the actions, and the goals. In other words, they make possible all the mechanics we

have seen so far and add the crucial thing that makes a game a game — goals.

Parlett's Rule Analysis

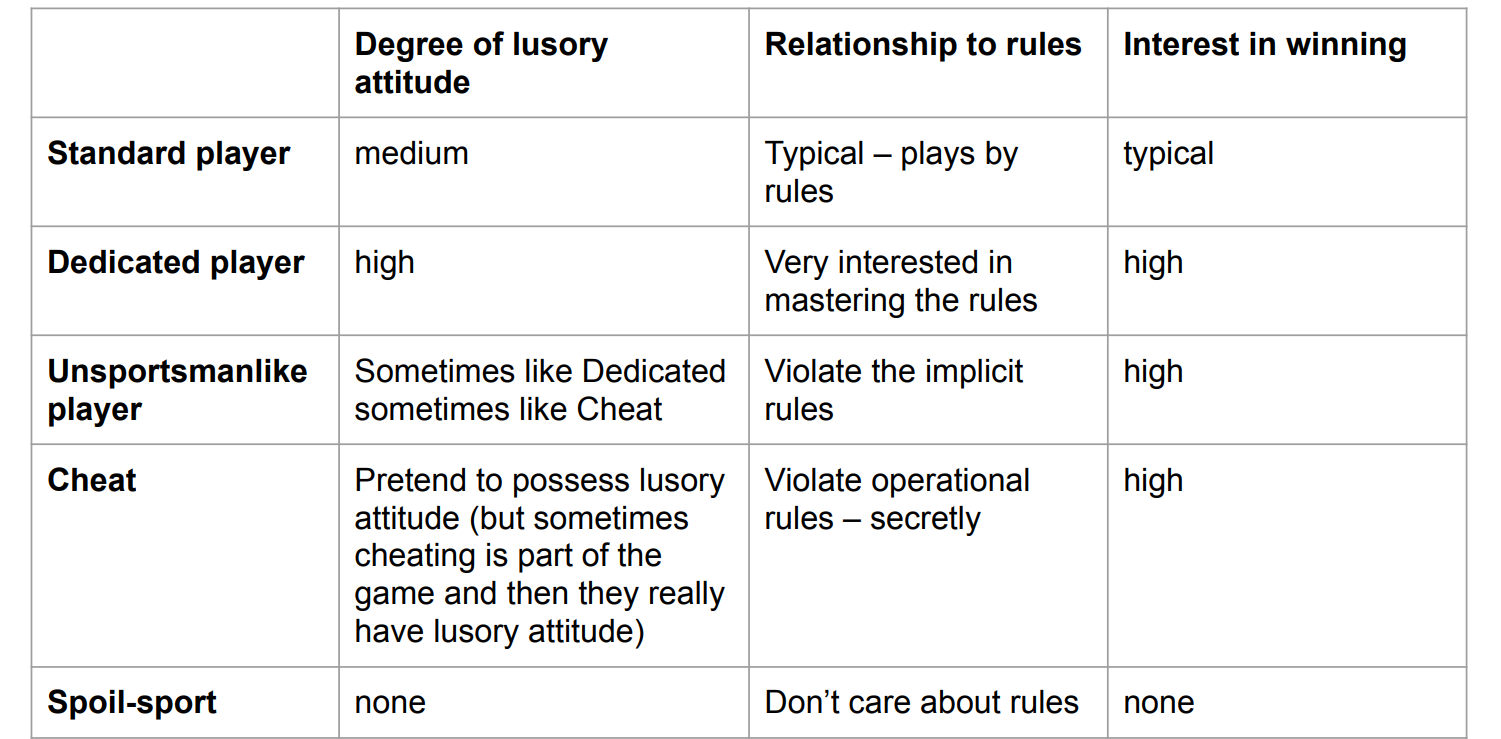

David Parlett, game historian, did a very good job of analyzing the different kinds of rules that are involved with gameplay, as shown in this diagram:

This shows the relationships between all the kinds of rules we are likely to encounter, so let's consider each.

- Operational rules: These are the easiest to understand. These are basically "What the players do to play the game". When players understand the operational rules, they can play a game.

- Foundational rules: The foundational rules are the underlying formal structure

of the game. The operational rules might say "The player should roll a six-sided

die, and collect that many power chips". The foundational rules would be more

abstract: "The player's power value is increased by a random number from 1 to

6".

Foundational rules are a mathematical representation of game state and how and when it changes. Boards, dice, chips, health meters, etc., are all just operational ways of keeping track of the foundational game state. As Parlett's diagram shows, foundational rules inform operational rules. There is not yet any standard notation for representing these rules, and there is some question about whether a complete notation is even possible.

In real life, game designers learn to see the foundational rules on an as-needed basis, but seldom do they have any need to formally document the entire set of foundational rules in a completely abstract way. - Behavioral rules: These are rules that are implicit to gameplay, which most people naturally understand as part of "good sportsmanship". For example, during a game of chess, one should not tickle the other player while they are trying to think or take five hours to make a move. These are seldom stated explicitly— mostly, everyone knows them. The fact that they exist underlines the point that a game is a kind of social contract between players. These, too, inform the operational rules.

- Written rules: These are the "rules that come with the game", the document that

players have to read to gain an understanding of the operational rules. Of course,

in reality, only a small number of people read this document—most people learn

a game by having someone else explain how to play. Why? It is very hard to

encode the nonlinear intricacies of how to play a game into a document and

similarly hard to decode such a document.

Modern video games have gradually been doing away with written rules in favor of having the game itself teach players how to play through interactive tutorials. This hands-on approach is far more effective, though it can be challenging and time consuming to design and implement as it involves many iterations that cannot be completed until the game is in its final state. Every game designer must have a ready answer to the question: "How will players learn to play my game?"" Because if someone can't figure out your game, they will not play it. - Laws: These are only formed when games are played in serious, competitive settings, where the stakes are high enough that a need is felt to explicitly record the rules of good sportsmanship or where there is need to clarify or modify the official written rules. These are often called "tournament rules", since during a serious tournament is when there is the most need for this kind of official clarification.

- Official rules: These are created when a game is played seriously enough that a group of players feels a need to merge the written rules with the laws. Over time, these official rules later become the written rules. In chess, when a player makes a move that puts the opponent's king in danger of checkmate, that player is obligated to warn the opponent by saying "check". At one time, this was a "law", not a written rule, but now it is part of the "official rules".

- Advisory rules: Often called "rules of strategy", these are just tips to help you play better, and not really "rules" at all from a game mechanics standpoint.

- House rules: These rules are not explicitly described by Parlett, but he does point out that as players play a game, they may find they want to tune the operational rules to make the game more fun. This is the "feedback" on his diagram, since house rules are usually created by players in response to a deficiency perceived after a few rounds of play

Modes

Many games have very different rules during different parts of play. The rules often change completely from mode to mode, almost like completely separate games.

One memorable instance was the racing game Pitstop. Most of the time, it was a typical racing game but with a twist—if you didn't pull over to change your tires periodically, they would burst. When you did pull over, the game changed completely— now you were not racing your car, but rather racing to change your tires, with a completely different game interface.

When your game changes modes in a dramatic way like this, it is very important that you let your players know which mode you are in. Too many modes and the players can get confused. Very often, there is one main mode, with several submodes, which is a good hierarchical way to organize the different modes.

Game designer Sid Meier proposes an excellent rule of thumb: players should never spend so much time in a subgame that they forget what they were doing in the main game.

Goals

Games have a lot of rules — how to move and what you can and cannot do — but there is one rule at the foundation of all the others: the object of the game.

Games are about achieving goals — you must be able to state your game's goal and state it clearly. Often, there is not just one goal in a game, but a sequence of them—you will need to state each and how they relate to one another.

When a goal is set in a player's mind, it gives them tremendous motivation to see it through. Having a clear set of well-constructed goals or quests is crucial to keeping your players engaged and motivated.

Good game goals are as follows:- Concrete: Players understand and can clearly state what they are supposed to achieve.

- Achievable: Players need to think that they have a chance of achieving the goal. If it seems impossible to them, they will quickly give up.

- Rewarding: A lot goes into making an achieved goal rewarding. If the goal has

the right level of challenge, just achieving it at all is a reward in itself. But why

not go further? You can make your goal even more rewarding by giving the

player something valuable upon reaching the goal.

And while it is important to reward players that achieve a goal, it is equally (or more) important that players appreciate that the goal is rewarding before they have achieved it, so that they are inspired to attempt to achieve it.

Don't overinflate their expectations, though, for if they are disappointed with the reward for achieving a goal, they will not play again!

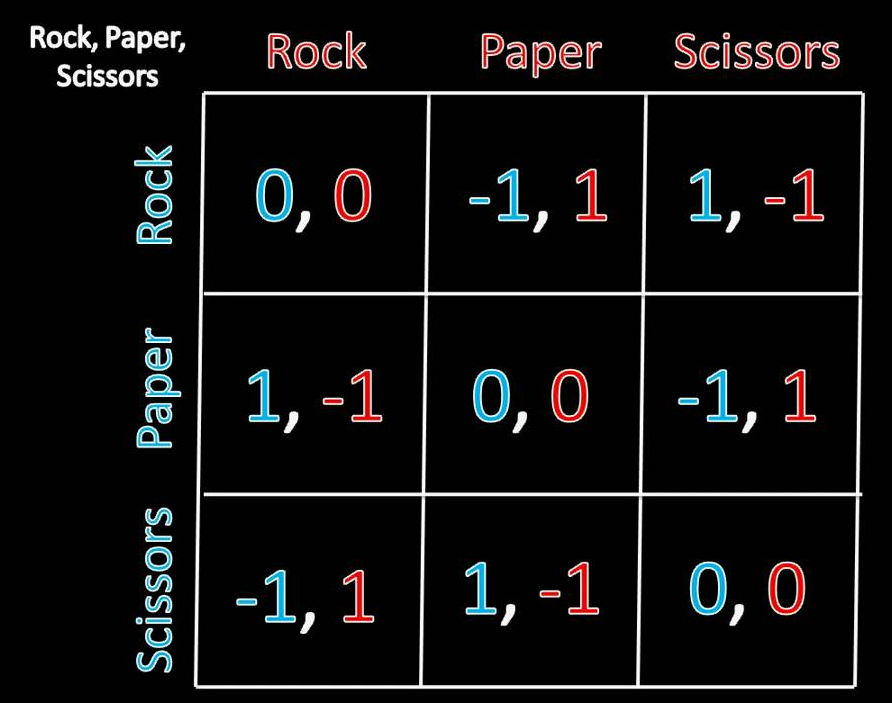

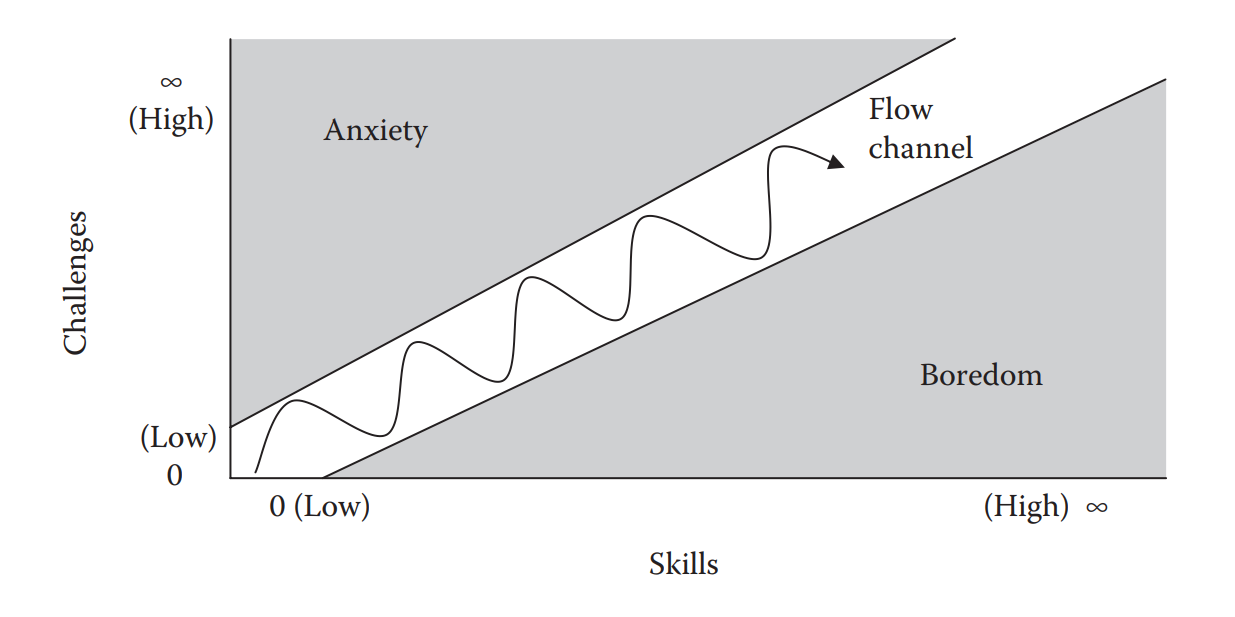

- Skill - The mechanic of skill shifts the focus away from the game and onto the player.

Every game requires players to exercise certain skills. If the player's skill level is a

good match to the game's difficulty, the player will feel challenged and stay in the

flow channel.

Most games do not just require one skill from a player — they require a blend of different skills. When you design a game, it is a worthwhile exercise to make a list of the skills that your game requires from the player.

Even though there are thousands of possible skills that can go into a game, skills can generally be divided into three main categories:- Physical skills: These include skills involving strength, dexterity, coordination, and physical endurance. Physical skills are an important part of most sports. Effectively manipulating a game controller is a kind of physical skill, but many video games (such as camera-based dance games) require a broader range of physical skills from players.

- Mental skills: These include the skills of memory, observation, and puzzle solving. Although some people shy away from games that require too much in the way of mental skills, it is the rare game that doesn't involve some mental skills, because games are interesting when there are interesting decisions to make, and decision making is a mental skill.

- Social skills: These include, among other things, reading an opponent (guessing what they are thinking), fooling an opponent, and coordinating with teammates. Typically, we think of social skills in terms of your ability to make friends and influence people, but the range of social and communication skills in games is much wider. Poker is largely a social game, because so much of it rests on concealing your thoughts and guessing the thoughts of others. Sports are very social, as well, with their focus on teamwork and on "psyching out" your opponents.

- Chance - Our seventh and final game mechanic is chance. We deal with it last because it

concerns interactions between all of the other six mechanics: space, time, objects,

actions, rules, and skills.

Chance is an essential part of a fun game because chance means uncertainty, and uncertainty means surprises. And as we have discussed earlier, surprises are an important source of human pleasure and the secret ingredient of fun.

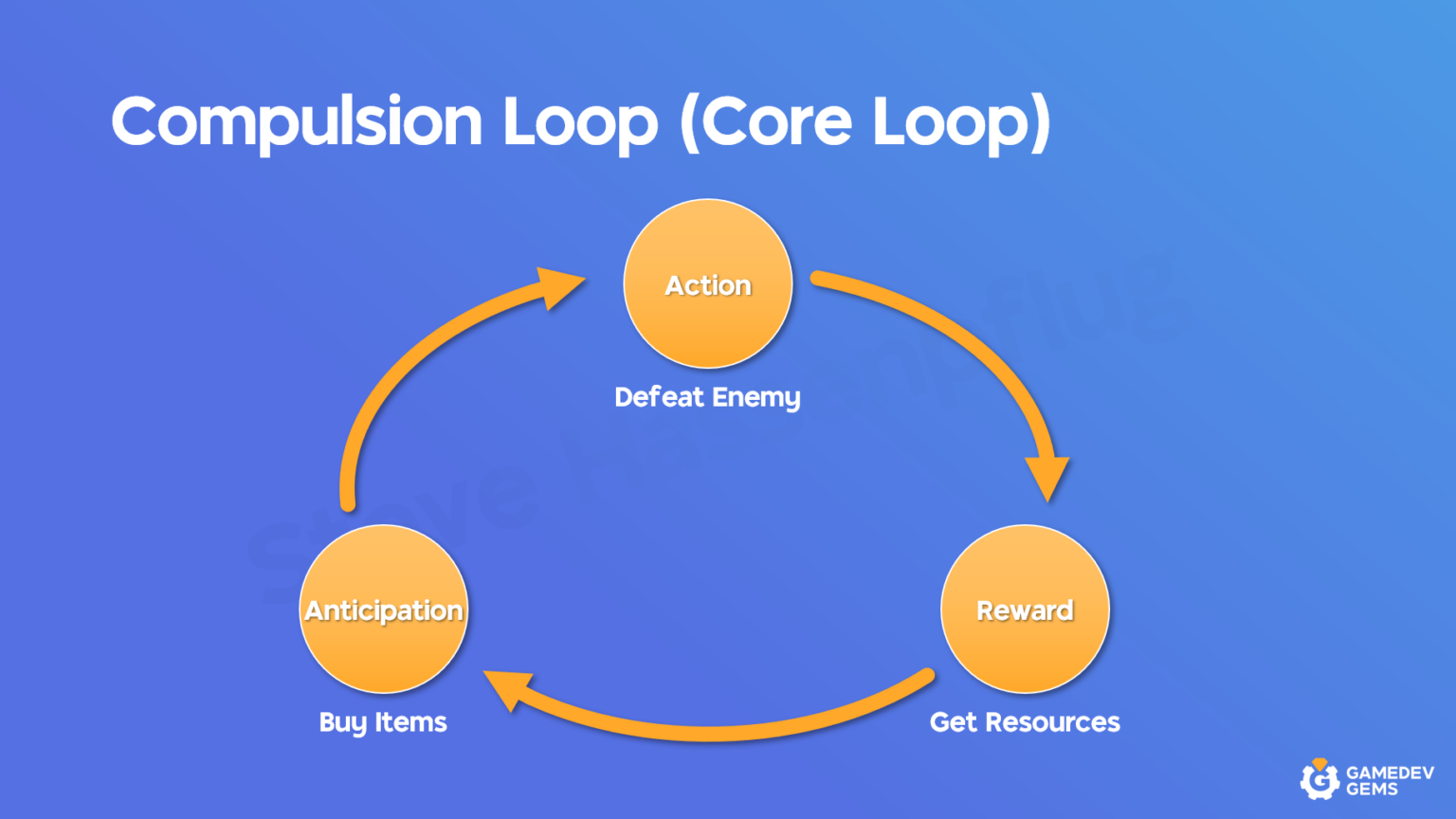

Designing your game mechanics based on player types

As we now know, there are four player types: Achievers, Explorers, Socializers, and Killers. Each type of player is motivated by different aspects of a game, and understanding these motivations can help you design game mechanics that cater to each player type.

Achievers

Their main goals consist of rising in status, scoring-points, and completing tasks. To provide achievers what they want, our game will mostly use extrinsic mechanics such as points and status, achievement symbols (badges, trophies, medals, crowns…), progress bars, fixed rewards and so on.

Here are few examples for such game mechanics:

- Points and scoring systems

- Levels and experience points (XP)

- Achievements and badges

- Leaderboards and rankings

Some board and tabletop games include:

- Collecting resources (e.g., in Settlers of Catan)

- Building structures or empires (e.g., in Carcassonne)

- Completing quests or missions (e.g., in Dungeons & Dragons)

Explorers

Explorers are motivated by discovery, learning, and understanding the game world. To engage explorers, our game will focus on intrinsic mechanics such as exploration, puzzles, and hidden content.

Here are few examples for such game mechanics:

- Branching choices

- Puzzles and riddles

- Lore and backstory

Some board and tabletop games include:

- Exploring a map or board (e.g., in Betrayal at House on the Hill)

- Uncovering hidden information (e.g., in Clue)

- Story-driven campaigns full of mysteries, locations to explore, and hidden lore (e.g., in Arkham Horror)

Socializers

Socializers thrive on interaction with other players. To cater to socializers, our game will incorporate mechanics that encourage collaboration, communication, and social interaction.

Here are few examples for such game mechanics:

- Chat and messaging systems

- Guilds or clans

- Cooperative gameplay

- Trading and gifting

Some board and tabletop games include:

- Team-based games (e.g., in Pandemic)

- Negotiation and alliances (e.g., in Diplomacy)

- Party games (e.g., in Codenames)

Killers

Killers enjoy competition and dominance over other players. To satisfy killers, our game will feature competitive mechanics such as PvP (player versus player) combat, leaderboards, and ranking systems.

Here are few examples for such game mechanics:

- PvP combat

- Leaderboards and rankings

- Competitive events and tournaments

- Achievements for defeating other players

Some board and tabletop games include:

- Direct player competition (e.g., in Risk)

- Elimination games (e.g., in Werewolf)

- Competitive card games (e.g., in Poker)

So let's talk about rules.

What are game rules? Let's begin with a simple example, one of the most minimal games we can find: Tic-Tac-Toe

The game of Tic-Tac-Toe is defined by the following set of rules:

- Play occurs on a 3 by 3 grid of 9 empty squares

- Two players take turns marking empty squares, the first player marking Xs and the second player marking Os

- If one player places three of the same marks in a row, that player wins

- If the spaces are all filled and there is no winner, the game ends in a draw

These four rules completely describe the formal system of Tic-Tac-Toe. They don't describe the experience of playing the game, they don't describe the history and culture of the game, but they do constitute the rules of the game. These four rules are all you need to begin playing a game of Tic-Tac-Toe.

Astonishingly enough, these simple rules have generated millions and millions of hours of game play. Armed with these rules, any two Tic-Tac-Toe players can be assured that when they begin play, they will both be playing the exact same game.

Whether played in front of a computer terminal or scratched in the sand of a beach, every game of Tic-Tac-Toe shares the same basic formal identity. In this sense, rules are the deep structure of a game from which all real-world instances of the game's play are derived.

Qualities of Rules

What are game rules like? What sets them apart from other kinds of rules? How do they function in a game? Consider the following list of rule characteristics:

- Rules limit player action: The chief way that rules operate is to limit the activities of players.

If you are playing the dice game Yatzee, think of all of the things you could do with the dice in that game: you could light them on fire eat them, juggle them, or make jewelry out of them. But you do not do any of these things. When you play a game of Yatzee, you follow the rules and do something incredibly narrow and specific. When it is your turn, you roll the dice and interpret their numerical results in particular ways.

Rules are "sets of instructions", and following those instructions means doing what the rules require and not doing something else instead. - Rules are explicit and unambiguous: Rules are complete and lack any ambiguity. For example, if

you were going to play a board game and it wasn't clear what to do when you landed on a particular

space, that ambiguity would have to be cleared up in order to play.

Similarly, rules have to be totally explicit in what they convey. If you were playing baseball in an abandoned lot and a tree was being used as second base, ambiguities regarding what counted as second base could lead to a collapse of the game. What can you touch and still be on second base? The roots? The branches? Or just the tree trunk? - Rules are shared by all players: In a game with many players all players share the same set of

rules.

If one player is operating under a set of rules different than the others, the game can break

down.

Take the abandoned lot baseball game example. If one player thinks that touching a branch of the tree is legally touching second base, but another player thinks that only the trunk is the base and tags the runner when he is holding onto a branch of the tree,is the player "out"? When the disagreement is raised, the game grinds to a halt. For the situation to be resolved, allowing the game to continue, all players must come to a common understanding of the rules and their application within play. It is not enough that rules are explicitly and unambiguously stated: the interpretation of the rules must also be shared. - Rules are fixed: The rules of a game are fixed and do not change as a game is played. If two

players

are playing a game of Chess and one of them suddenly announces a new rule that one of her own

pawns is invulnerable, the other player would most likely protest this sudden rule improvisation.

There are many games in which changing the rules is part of the game in some way; however, the way rules can be modified is always highly regulated. In professional sports, for example, changes to rules must pass through a legislative process by governing organizations.

Even in games in which the rules are changed during play itself, such as the whimsical card game Flux (in which playing a card can change the overall game's goals and rules), the ways the rules change are quite limited and are themselves determined by other, more fundamental rules. - Rules are binding: Rules are meant to be followed. The reason why the rules of a game can remain

fixed and shared is

because they are ultimately binding. In some games, the authority of the rules is manifest in the

persona of the referee.

Like the rules themselves, the referee has an authority beyond that of an ordinary player. If players did not feel that rules were binding, they would feel free to cheat or to leave the game as a "spoil sport". - Rules are repeatable: Rules are repeatable from game to game and are portable between sets of

different players. In a Magic: The Gathering tournament, all the players in the tournament follow the

same rules when they square off against each other. Outside of the limited context of an individual

tournament, the game rules are equally repeatable and portable.

Although games often have "home rules," such as the many different versions of rules for the "Free Parking" space in Monopoly, these rule variants are just local variants on largely consistent rule sets. In any case, players must resolve ambiguities between sets of "home rules" in order to play a game.

These qualities of rules are in operation whenever one plays a game. If any of these qualities are not in effect, the game system may break down, making play impossible. If rules are ambiguous, players must resolve the ambiguities before play begins. If rules are not binding, players won't respect their authority and might cheat.

Rules and Strategy

One note of clarification about the difference between the rules of a game and rules of strategy: rules as we understand them here as the formal structure of a game are not the same thing as strategies for play, even though the two might seem similar.

While playing Tic-Tac-Toe, you might devise a "rule of thumb" to assist your play. For example, if your opponent is about to win, you need to place a mark that will block your opponent. This kind of strategic "rule" is an important aspect of games (for example, you might use rules like this to program a computer opponent for a Tic-Tac-Toe game), but these rules of strategy are not part of the formal rules of the game.

The actual game rules are the core formal system that constitutes how a game functions. Rules that help players perform better are not a part of this formal system.

Do these four rules specified constitute the complete formal system of Tic-Tac-Toe?

Although these rules do describe to players what they need to know in order to play, there are aspects of the formal system of Tic-Tac-Toe that are not included here.

Specifically, there are two kinds of formal structures that these four rules do not completely cover: the underlying mathematical structures of the game and the implied rules of game etiquette.

Let us explore these two kinds of formal structures one at a time. First, there is the foundational formal structure that lies "under the hood" of the rules of Tic-Tac-Toe. Does such a structure exist? Is it different than the stated rules of play? There is, in fact, a core mathematical logic that is part of every game but that is not necessarily expressed directly in the stated rules of the game that a player must learn.

To understand this point, take a look at a game thought experiment by Marc LeBlanc. The game is called 3-to-15.

Rules for 3-to-15:

- Two players alternate turns

- On your turn, pick a number from 1 to 9

- You may not pick a number that has already been picked by either player. If you have a set of exactly 3 numbers that sum to 15, you win

What does this game have to do with Tic-Tac-Toe? At first glance, 3-to-15 doesn't seem anything like Tic-Tac-Toe. Instead of making Xs and Os, players are picking numbers. There is not even mention of a grid.

But if you look more closely, you will see that 3-to-15 is really just a disguised version of Tic-Tac-Toe. The numbers 1 to 9 can be arranged in a 3 by 3 grid like this:

8 | 1 | 6

---------

3 | 5 | 7

---------

4 | 9 | 2The underlying rules found in both Tic-Tac-Toe and 3-to-15 look something like this:

- Two players alternate making a unique selection from a grid array of 3 by 3 units.

- The first player to select three units in a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal row is the winner

- If no player can make a selection and there is no winner, then the game ends in a draw

These "rules" resemble both the rules of Tic-Tac-Toe and 3-to-15, with some significant differences. For example, the rules don't mention how the player makes a selection from the array of choices, or how to record a player's action. The rules above are a kind of abstraction of both games.

Questions remain: is 3-to-15 a variant of Tic-Tac-Toe or a different game entirely? If it is a different game, what does it share with Tic-Tac-Toe? What does all of this say about the "rules" of Tic-Tac-Toe?

For the time being, just note that there are in fact formal aspects of games such as Tic-Tac-Toe that lie underneath the stated "rules of play".

Three Kinds of Rules

As the example of Tic-Tac-Toe demonstrates, in order to fully understand the formal operation of a game, we need to complexify our understanding of game rules. We propose a three-part system for understanding what game rules are and how they operate.

- Operational rules: the "rules of play" of a game.They are what we normally think of as rules: the

guidelines

players require in order to play. The operational rules are usually synonymous with the written-out "rules"

that

accompany board games and other non-digital games.

The operational rules of Tic-Tac-Toe are the four rules we initially presented - Constitutive rules: the underlying formal structures that exist "below the surface" of the

rules presented to players. These formal structures are logical and mathematical.

In the case of Tic-Tac-Toe, the constitutive rules are the underlying mathematical logic that Tic-Tac-Toe shares with the game 3-to-15. - Implicit rules: the "unwritten rules" of a game. These rules concern etiquette, good sportsmanship,

and

other implied rules of proper game behavior. The number of implicit rules of Tic-Tac-Toe is vast and cannot

be completely listed.

The implicit rules of Tic-Tac-Toe are similar to the implicit rules of other turn-based games such as Chess. However, implicit rules can change from game to game and from context to context.

For example, you might let a young child "take back" a foolish move in a game of Chess, but you probably wouldn't let your opponent do the same in a hotly contested grudge match.

The operational rules for any particular game build directly on that game's constitutive rules. However, any given set of constitutive rules can be expressed in many different operational forms.

There is a fuzzy boundary between operational and implicit rules. For example, sometimes a game designer may make certain implicit rules explicit by including them in the printed rules of a game

The Rules of Chutes and Ladders

Now that we have taken a closer look at the formal structure of Tic-Tac-Toe, it is clear that the phenomenon of game rules is more complex than it initially appeared.

Let us continue our investigation of three kinds of rules by turning to the board game Chutes and Ladders.

The printed rules of the game read as follows: Chutes and Ladders rules

How do these printed rules relate to the operational, constitutive, and implicit rules of the game?

Operational Rules of Chutes and Ladders

The operational rules of Chutes and Ladders are mostly contained in the printed rules. The operational rules are explicit instructions that guide the behavior of players. How to Play rule number two, for example, tells players: "On your turn, spin the spinner and move your pawn, square by square, the number shown on the spinner."